The Power Broker

Robert Moses and re-making the political machine

I recently finished The Power Broker by Robert Caro, an epic study on power profiling the arc of Robert Moses. Moses was probably the most prolific builder of public works in American history. He conceived and completed works in New York that cost $27B (in 1968 dollars), including 13 bridges (e.g., Triborough), 416 miles of parkway (e.g., the Westside Highway), parks (e.g, Jones Beach), 658 playgrounds, 1082 housing project, power (e.g., Niagara and St. Lawrence), the UN, Lincoln Center, and Shea Stadium.

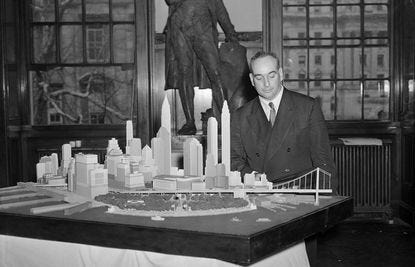

The most interesting aspect of Moses was that he ran an organization, the Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority, that functioned like a shadow government with its own flag, license plate, constitution, police force, communications network, revenue, and base at Randall’s Island (pictured below). Through Triborough, Moses ran a fascinating political machine. Below are a few of the masterstrokes employed in his 40 year reign, which lasted through the administrations of five NYC mayors and six NY governors.

Masterstroke #1: He won over the press and public

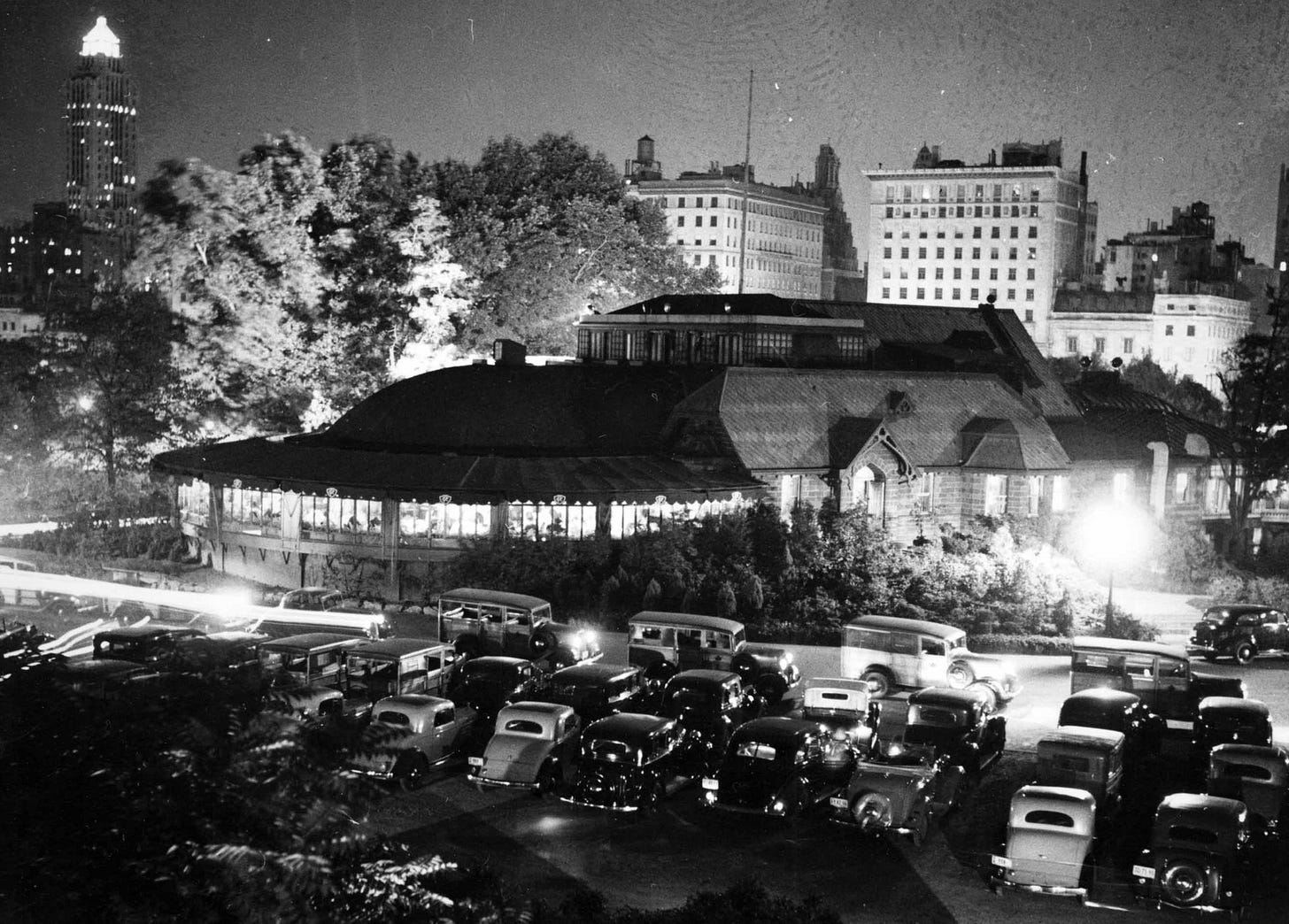

His entry point to power was parks in the mid 1920s. Parks were a wise place to start because the city was heavily under-served: Coney Island was the only access to beach for many in NYC and was poorly staffed with Tammany patronage (e.g., elderly and / or obese lifeguards that could not swim). “First aid stations” at city beaches were filled with prostitutes. Two parks and four playground served 500k people on the Lower East Side. By 1932, Central Park had suffered from 60 years of neglect. People donated pets to the Zoo and its main attractions included a senile tiger, a semi-paralyzed baboon, a puma with rickets, rats that stole food from the animals, and a flock of inbred sheep. Tammany mayor Jimmy Walker even built a casino in Central Park (below).

Along with parks, Moses began building parkways at a time when the city had failed to keep up with the growth in cars. By 1916, eight years after Henry Ford's first Model T, the intersection of 5th and 57th had ~15k cars and carriages per day (similar to today). Between 1918 and 1932, NYC cars grew from ~125k to ~700k, but no highways existed and no bridges had been built in 25 years. The bridges that did exist were designed for horses with narrow lanes and slick surfaces. The Broadway drawbridge to the Bronx had to be raised over a dozen times per day. Ferries had to supplement bridges and the city was chocked with traffic because there were no highways or bypasses routes.

Against this backdrop, Moses prolifically built parks and highways via numerous appointed commissions in the 20s and 30s. This made him a folk hero with the public and press who called him “a selfless servant of the people.” Moses himself said it best:

As long as you’re on the side of the parks, you’re on the side of the angels. You can’t lose.

Masterstroke #2: He secured his funding

Prior to Moses, public authorities were temporary agencies used to finance public works: they issued bonds to finance a project, collected revenues (e.g., from tolls), and disbanded when the bondholders were paid back. Moses drafted amendments in the Triborough Authority act that allowed Triborough to pass resolutions governing the sale of its bonds. This was genius. Resolutions could bake in arbitrary provisions (e.g., the right to collect bridge tolls for perpetuity). And bonds were contracts, which were protected by the Constitution Article I, Section 10: no state shall pass any law that impairs the obligation of contracts. Provisions that Moses wrote into the bond covenants could not be amended except by consent of the parties to the contract, as Caro says:

Robert Moses still had his immense popularity. But were he to lose that popularity, the loss would no longer be as disastrous as it would have been in the past. For no one — not the people, elected representatives, or courts — could change those covenants.

Through tolls and bond sales, Moses created his own “venture capital” fund for public infrastructure, using existing proceeds to finance new projects. As cars in NYC grew from ~11M in 1941 to ~46M in 1960, annual Triborough income grew by 10-fold from ~8M in 1941 to, with the Verrazano bride open and operating at $0.50 per car, ~$75M in 1967. He supplemented this income with bond sales, giving him $750M to spend.

And this spending was done in secrecy. Moses used his ties with the press to promote the idea that Triborough was honest and apolitical. Around 1400 editorials between 1946 and 1951 praised public authorities as prudent, honest, and efficient. Dorothy Schiff at the NYT tried to audit Triborough, but was blocked by Moses and the courts:

No one could disprove Moses reputation without first opening Triborough’s books. And no one could open Triborough’s books without first disproving Moses reputation.

Masterstroke #3: He re-shaped the political machine

In the years before social welfare programs, political machines such as Tammany Hall provided services (e.g., holiday turkeys, coal in winter, and ice in summer), favors (e.g., city contracts for associates) and patronage jobs. In return, Tammany expected votes for its handpicked candidates. Charles “Silent Charlie” Murphy was the longest-reigning boss of Tammany from 1902 until 1924. If you were a voter in his district and didn’t come to the polls, you got a handwritten note delivered to your door: “Oh, by the way, haven’t you forgotten to do something, and remember all those things I did for you?”

Tammany politician George W. Plunkitt famously explained the different types of graft in the machine. “I’ve made a big fortune out of the game, but I’ve not gone in for dishonest graft — blackmailin’ gamblers, saloon-keepers, disorderly people.” In contrast, early access to construction plans was considered honest graft: contracts could be steered to firms owned by politicians or, if Plunkitt learned where a park or a bridge was going to be built, he’d “go to that place and buy up all the land (he could) in the neighborhood.”

Between the founding of modern Tammany in the 1850s and the inauguration of La Guardia in 1934, anti-Tammany reformers held power for only ~10 years:

“Tammany is not a wave,” a chief of police explained, “it’s the sea itself.”

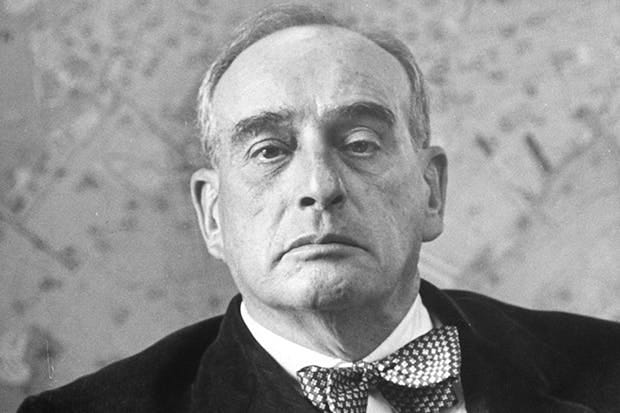

But reform mayor La Guardia diverted federal relief funds, a prime source of graft, through his own lieutenants in city hall, starving out Tammany. This resulted in bad times for Tammany; membership in its clubs fell 70% in La Guardia’s first term. Into this vacuum, then, Robert Moses moved. As Caro explains about Moses (pictured):

He was political boss with a difference: His constituency was not the public but some of the most powerful men in the city and state, and he kept these men in line by doling out to them, as Tammany ward bosses once handed out turkeys at Thanksgiving.

In addition to the press, below are other key constituents that Moses carefully aligned.

Tammany Hall

Moses created a system that substituted his projects with the traditional means by which the machine grew fat. He needed Tammany because its Borough presidents sat on the NYC Board of Estimate, which made land use decisions. Tammany needed jobs for unions and honest graft. Under La Guardia, federal money was subject to audit, but the ample Triborough money was famously not. So, Moses projects were a package with everything that the machine wanted including contracts, PR retainers, insurance premiums, and legal fees directed wherever the bosses desired. Moses even gave patronage. Every spring, word went out from the Park Department to district leaders to get the names in for Park Department summer jobs. As explained by one leader:

Some guys had a lifetime summer jobs. They were 70 years old.

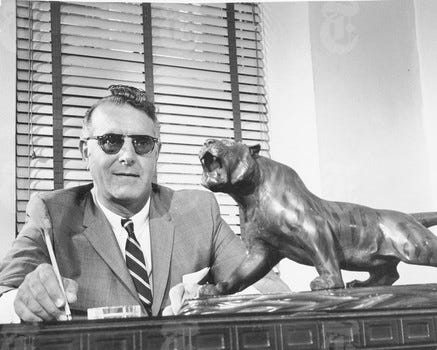

In exchange, ward bosses had had to agree to the Moses public work as it was. And for 20 postwar years, most NYC elected officials were products of the machine that Moses fed. By 1953, 3 of the 5 Tammany bosses were on his payroll. This included Stanley Steingut (Brooklyn boss), the greatest checker mover in town. Young Stanley cast his first vote at age six. This also included Edward Flynn (Bronx) whose memoir You're the Boss was published in 1947. And it included Carmine De Sapio (below), the youngest boss in the history of Tammany Hall. This anecdote illustrates De Sapio’s influence:

Once he was booked for an appearance at NYU on Yom Kippur. Fearing low turn-out, De Sapio’s lieutenants secretly recruited an audience of sanitation workers and gave them college-style crew cuts and tweed jackets so as to not disappoint their boss.

Politicians

Working for governor Al Smith in 1919, Moses had re-designed much of the NY state government as part of reconstruction commission. So, he knew which positions were crucial and pushed to have Moses men in all critical posts. But, in cases when he didn’t, he ensured that all of the secretaries were on his payroll. They sent copies of relevant legislation to Moses representatives. He also had a crew of hired “bloodhounds” to dredge up secrets on politicians. He destroyed the careers of numerous politicians (e.g., Stanley Isaacs and Rexford Tugwell) and provided the press with “information” for both of the widespread communist witchhunts in NYC in 1938 and 1958.

Banks

After the depression, NYC banks were desperate for “good paper.” And Moses public authority bonds were the best investments banks could make: corporate profits were more risky than bridge tolls and Triborough bonds were tax exempt. Moses let banks under-write Triborough bond issues and each postwar issue was sold out. Moses was also generous. For example, he let the Verrazano syndicate buy $300M in bonds for $295M and sell the same day for immediate profit. Chase Manhattan Bank, the most powerful financial institution on earth then, was selected by Moses as the trustee of Triborough bonds and Chase president David Rockafeller was close with Moses. In turn, Moses used bankers to force public officials to support all Triborough projects.

Unions

In the postwar era, unions were a key part of the Democratic machine and leaders like Pete Brennan (below) had significant power to influence government. Of union men, Murray Kempton said a construction worker would pave over his grandmother if the job paid $3.50 / hour. A primary concern was where next years work would come for the large (e.g., 255k member) unions. Public works were a good source of labor. The Verrazano took, for example, ~1200 men per day for 5 years. So, union leaders were pressed for new public works and Moses was obliged to deliver. Pete Brennan said of Moses:

The thing about Moses is he’s a guy who gets things done.

Legacy

By first gaining favor with the press and then using that goodwill to protect a public authority that collected and distributed large sums of capital in secret, Moses fed the needs of bankers (good paper bonds), Tammany (honest graft), and unions (jobs) at the same time. The output of all of this was a prolific set of public works. Interestingly, Moses himself did not get rich. He put everything back into more power acquisition for more public works. At his peak, he held twelve simultaneous city and state posts.

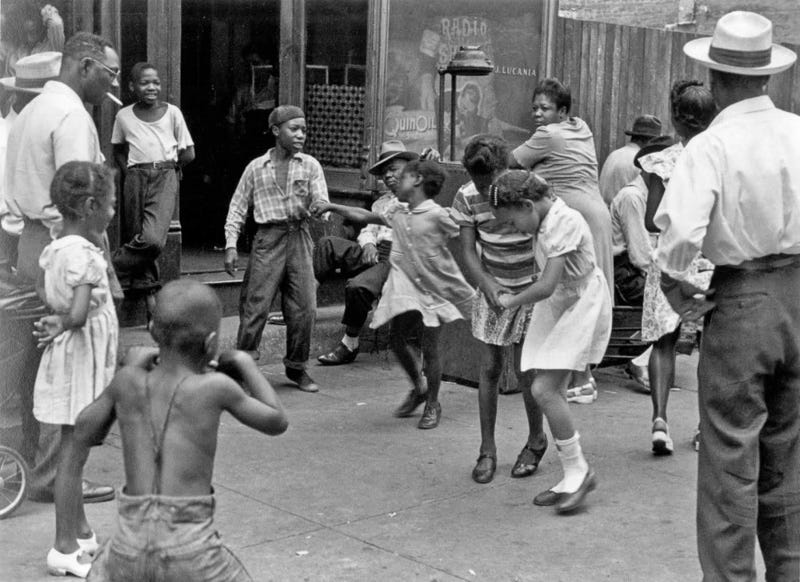

That said, Caro makes a convincing case that Moses was a terrible person. He was racist, famously built bridges that were too low for buses to restrict the access of poor New Yorkers, and left a terrible legacy of urban renewal. His slum clearance destroyed thriving neighborhoods, replacing the dynamism of street life (beautifully chronicled in this film by Helen Levitt and shown below) with Corbusian high-density towers on broad concrete plazas, which have become a well studied disaster of modernism.

Even still, his arc is a fascinating study in power and political machines. And Ed Glaser has a reasonable take on Moses here: there are some things to be admired from his prolific ability to build and, perhaps, the pendulum has swung to far when we consider cities like San Francisco suffering from an inability to build at all.